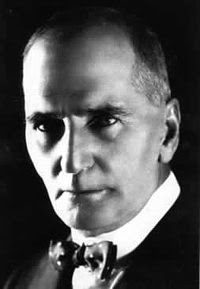

Eugene Marais was born in a farming community near Pretoria in 1872. Educated in the Transvaal, Orange Free State and Cape Province, he made journalism his first career.

By 1890, he was editor of the newspaper Land en Volk, and two years later, at the age of 21, he owned it.

In 1894 he married, only to see his young wife, Jacoba, die the following the year, in July 1895, at the age of 23, following the birth of their son. This was a tragic loss from which he never recovered.

Shortly afterwards he moved to London, where he studied law and medicine. By the time he was admitted to the bar at the Inner Temple, the Boer War was in progress, and Marais set out to return to Africa to assist his countrymen (although the war ended before he could make his way home).

In 1910, he went to Johannesburg to establish himself as an advocate, but increasing depression of spirits drove him to retreat to Waterberg, a mountain area in northern Transvaal. Settling near a large group of chacma baboons, he became the first man to conduct a prolonged study of the primates in the wild. It was during this period that he produced My Friends the Baboons, and gathered the material for the later and more scientific work The Soul of the Ape.

My Friends the Baboons is that rare piece of writing; a paper of scientific observation which is also a deeply personal journal. Who could not be moved by the final chapter, for example, when a tribe of baboons appeals to Marais and his companion to save their young from imminent death?

Marais, by now a journalist, poet, scholar and scientist, spent more than three years studying the chacma baboons in the wild, and his notes, comments and conclusions have been a source of inspiration since they were written. He was able to study a troop of baboons who had never known man. The four-year Boer War had removed the settlers, and the baboon troop led an undisturbed life, with no fear of their modern and most devastating foe: human farmers.

Marais was indeed fortunate in being able to watch this animal society in a natural environment. His observations of how they organised their lives together, how they expressed themselves, and above all, their instinctive reactions, allowed him to draw conclusions on the development of animal and human psyche which caused – and continue to cause – debate in scientific circles.

His ideas are as pertinent today as they ever were.

The keenness of his observations is magnificently matched by his compassionate prose. His ideas are expressed in language so eloquently moving that the very style of the book makes it a treasure to read.

The Soul of the Ape is the more scientific record of his experiences and observations. Lost for forty years, the manuscript was rediscovered by Robert Ardrey, who dedicated his book African Genesis to Marais. Ardrey believed that Marais’ work “presents better than any other book published thus far the dawning of humanity in the psyche of the higher primate.”

Together, these two works are both a rare personal document, a journal of scientific observation, and a pioneering study of the primitive mind.

Doris Lessing wrote in The New Statesman:

“He offers a vision of nature as a whole, whose parts obey different time-laws, move in affinities and linkages we could learn to see: parts making wholes on their own level, but seen by our divisive brains as a multitude of individualities, a flock of birds, a species of plant or beast. We are just at the start of an understanding of the heavens as a web of interlocking clocks, all differently set: an understanding that is not intellectual, but woven into experience. Marais brings this thought down into the plain, the hedgerow, the garden.”

After the period dealt with in the movie Die Wonderwerker (see below), Marais returned to Pretoria to practice law, to resume his animal studies, to struggle with opiate addiction, and to write poetry in Afrikaans. (He could write in English, but preferred not to, because of his disgust at the conduct of the British during the Boer War.)

In 1926, the year after he had published a definitive text on his original and ground-breaking conclusions about the white ant – The Soul of the White Ant – the famous European writer Maurice Maeterlinck stole half of Marais’ work, and published it as his own. Out of dignity, Marais refused to sue, but the episode distressed and damaged him deeply, and it is quite probable that the stress of it contributed to his collapse. This final and difficult period of Marais’ life is discussed in detail in Robert Ardrey’s introduction to The Soul of the Ape.

After years of increasing difficulties with morphine, depression and anxiety, Eugene Marais took his own life in 1936.

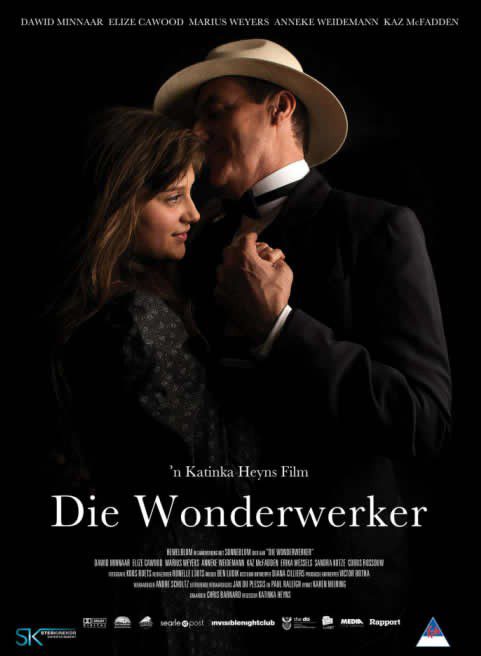

Die Wonderwerker

Die Wonderwerker is a popular recent film by Katinka Heyns, in Afrikaans with English subtitles. It revolves around an episode in the early life of Marais. After spending years in the wild studying baboons and ants, he arrives at a farm looking for water. He is in a bad way, so the farmer takes him in so he can recover. It isn’t long before the farmer’s wife falls in love with him, but he is more attracted to the farmer’s young adopted daughter, who has another admirer of her own. This complex romantic quadrangle gets even more complicated when the farmer’s wife discovers his morphine habit, and starts rationing it out to him.

The film’s IMDB page is here.

Videos

For over three decades, Dr. Robert Sapolsky has been working to advance our understanding of stress — in particular how our various hierarchies can make us more or less susceptible to the damaging effects of stress.

“Primates are super smart and organized just enough to devote their free time to being miserable to each other and stressing each other out,” he said. “But if you get chronically, psychosocially stressed, you’re going to compromise your health. So, essentially, we’ve evolved to be smart enough to make ourselves sick.”

Sapolsky, a neuroendocrinologist, found that baboons with lower social ranks had higher levels of stress hormones which can cause problems with blood pressure, the immune and reproductive systems, and brain chemistry resembling that of the clinically depressed.

Baboon troops usually have strong social hierarchy, with alpha males going around beating the shit out of lesser baboons and sexually assaulting the females.

Nature 2018 HD Documentary. Kasanka National Park in Zambia is home to an unusual species of baboon.

Eugène Nielen Marais was a pioneer of animal behaviour and has been described as having advanced it by many decades.

Australian journo Tim Noonan travels to Cape Town in South Africa to cover a neighbourhood dispute of a different kind. On one side, the baboon residents who have been there for a million years … on the other, their human neighbours who are moving in. It all started when people began building on prime land belonging to the local baboons and naturally the primates took it very personally responding with a crime wave of carjackings, muggings and home invasions. This is the real-life version of planet of the apes!

This is an odd one. Whenever baboon troop leader Papio struts from the no man’s land between Zimbabwe and South Africa, he does so with the audacity of a Mafia Don. Crossing the border, no one dares block his path – neither the armed guards nor the border officials. For Don Papio, times are good. His brutal campaign of ambushes and incursions have finally paid off…

Books

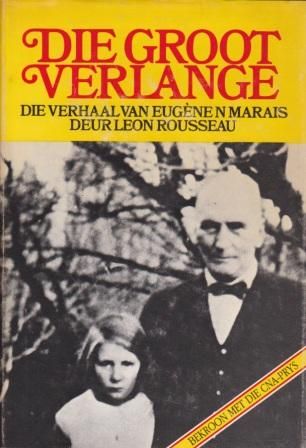

Die Groot Verlange: Die verhaal van Eugene N. Marais (The Story of Eugene Marais) by Leon Rousseau. See this book (Afrikaans) on Abe Books. The Afrikaans version was published in 1974 by Human and Rousseau.

The English version of Roussaeu's book is entitled The Dark Stream, and was published in 1999 by Jonathan Ball. There is a confronting discussion of it on the Mail & Guardian site by Stephen Gray. There is more information on its GoodReads page.

The Soul of the Ape & My Friends the Baboons

A Distant Mirror has published new editions of Marais’ two works on baboons combined together in one 300 page, illustrated paperback. Details of The Soul of the Ape & My Friends the Baboons are here.

The Soul of the White Ant

In his last work, The Soul of the White Ant, Marais created a passionate, insightful account into the world of termites. It is a meticulously researched expose of their complex, highly structured community life.

Originally translated into English in 1937, the quality of research remains as relevant today as it was when it was first published.

An exceptional feature of his detailed research is the extraordinary psychological life of the termite. While the studies are based in South Africa, the research also includes the termites of Magnetic Island, Australia.

The Soul of the White Ant is part science, part mysticism, a sort of manual of pantheism, and a very personal and careful observation of termites as a life form.

“As a safari Guide in the Okavango Botswana for many years, I used this book as a basis for presenting a fascination for the smaller creatures of the African bush, my home for my entire life and which I was privileged to share with many clients from different countries. Termite mounds are really interesting and Eugene Marais compared the infrastructure of a termitary to that of the human body. Writing from the heart, this scientific author instills a wonder in the reader, of the incredible intricacies of nature, in a light-hearted, easily readable manner.”

“An excellent read – astonishing for it’s time. A heartfelt and truly holistic/metaphysical observation of how the colony functions which is deeply thought provoking…”

Be the first to comment