Key concepts

- Who was Antoine Bechamp? A highly respected 19th-century French scientist and a rival to Louis Pasteur.

- What is the Microzyma Theory? Bechamps theory that “microzymas” (tiny living entities) are the fundamental building blocks of all life, capable of transforming into bacteria to break down a dying organism.

- What is the “Terrain Theory”? The Bechamp-aligned idea that the condition of the body (the “terrain”) is more important than the “germs” that inhabit it.

- Why the Controversy? Pasteur’s “Germ Theory” won out politically, leading to Bechamp’s work being suppressed and “unpersoned” from scientific history for over a century.

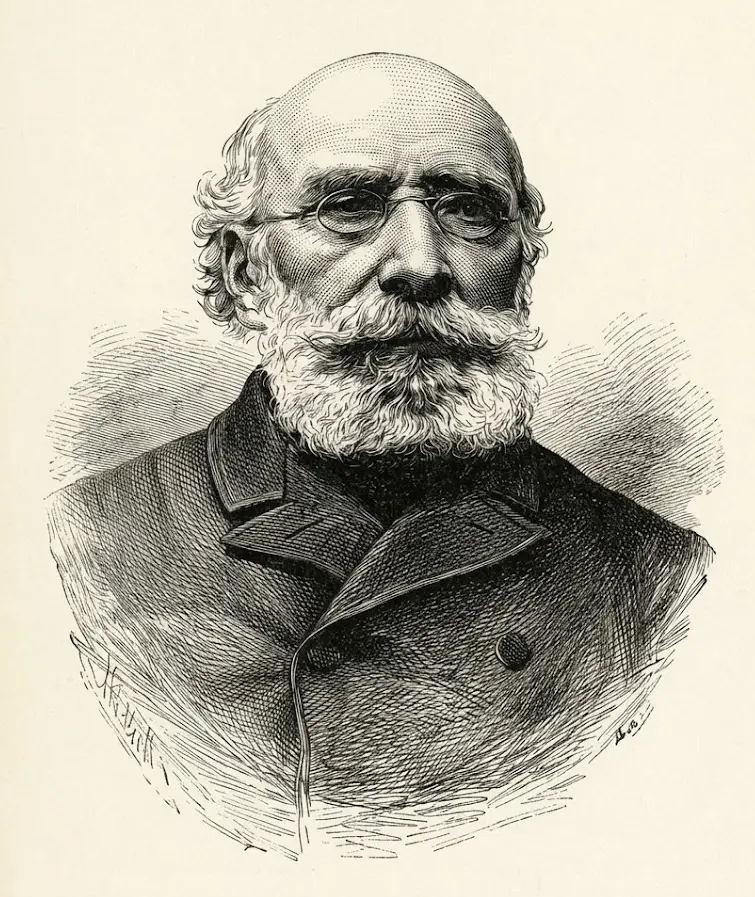

Antoine Béchamp (1816–1908) was a brilliant 19th-century French scientist, professor, and member of the French Academy of Sciences. A contemporary and bitter rival of Louis Pasteur, Béchamp’s groundbreaking work offered a radically different view of biology and disease that challenged the “Germ Theory” which dominates modern medicine.

- The Microzyma Theory: Béchamp discovered tiny, indestructible living entities he called “microzymas” (or “little ferments”) which he identified as the fundamental building blocks of all life. He proposed that these entities build cells and, upon death, break them down to be recycled by nature.

- The “Terrain” Theory: While Pasteur focused on the germ as the enemy, Béchamp argued that the “terrain” (the internal environment of the body) determines health. He believed that disease arises when the body’s balance is disturbed, causing endogenous microzymas to transform into bacteria to clean up the toxic environment.

- Pleomorphism: The concept that microorganisms can change form (morph) through different life cycles based on their environment, a direct contradiction to the fixed “monomorphic” view of bacteria held by Pasteur.

Legacy: Despite his profound contributions, Béchamp’s work was politically sidelined in favor of Pasteur’s more commercially viable theories. Today, his research is being rediscovered by scientists and researchers exploring the complexities of the microbiome and epigenetics.

ANTOINE BECHAMP (1816–1908) was a giant of 19th-century science whose discoveries challenged the very foundation of modern biology. A contemporary and bitter rival of Louis Pasteur, Bechamp proposed the “Microzyma” theory—a revolutionary perspective that prioritized the internal biological terrain over the germ itself. Yet, despite his profound contributions, his legacy was systematically erased from history. This definitive guide restores that lost record, exploring the life, the controversy, and the enduring science of a man who was far ahead of his time.

Introduction

During his lifetime, Antoine Bechamp (1816-1908) was a well-known and widely respected professor, teacher, and researcher. He was an active member of the French Academy of Sciences, and gave many presentations there during his long career. He also published many papers, all of which still exist and are available.

Yet for many decades, he largely disappeared from history – although that has changed in the last 20 years or so.

On the other hand, Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) is one of the rock stars of medicine and biology. Of the two – Bechamp or Pasteur – he’s the one you’ve most likely heard of. His is one of the most recognizable names in modern science. Many discoveries and advances in medicine and microbiology are attributed to him, including vaccination, and the centrepiece of his science – the germ theory of disease.

During their lifetimes, the rivalry between Bechamp and Pasteur was constant, and often bitter. They clashed frequently both in speeches before the Academy, and in papers presented to it. Bechamp repeatedly showed that Pasteur’s ‘findings’ included frequent plagiarizations (and distortions) of Bechamp’s own work.

When Bechamp and others objected to the plagiarization, Pasteur set out to use his political clout to destroy Bechamp’s career and reputation. Pasteur largely succeeded. He was more skilful than Bechamp at playing politics and attending the right functions. He was good at making friends in high circles, and was popular with the royal family.

Pasteur, in other words, was an A-lister. Bechamp was a worker.

The ideas, as well as the characters, of the two men were fundamentally opposed.

Pasteur argued for what we now call the ‘germ theory’ of disease, while Bechamp’s work sought to confirm pleomorphism; the idea that all life is based on the forms that a certain class of organisms take during the various stages of their life-cycles.

This difference is fundamental. Bechamp believed that his work showed the connection between science and religion – the one a search after truth, and the other the effort to live up to individual belief. It is fitting that his book Les Mycrozymas (which has not been translated into English) culminates in the acclamation of God as the Supreme Source. Bechamp’s teachings are in direct opposition to the materialistic views of the modern science of the twentieth century.

“These microorganisms (germs) feed upon the poisonous material which they find in the sick organism and prepare it for excretion. These tiny organisms are derived from still tinier organisms called microzyma. These microzyma are present in the tissues and blood of all living organisms where they remain normally quiescent and harmless. When the welfare of the human body is threatened by the presence of potentially harmful material, a transmutation takes place. The microzyma changes into a bacterium or virus which immediately goes to work to rid the body of this harmful material. When the bacteria or viruses have completed their task of consuming the harmful material they automatically revert to the microzyma stage” – Antoine Bechamp

Béchamp found his microscopic particles and their activites everywhere in nature. They appeared in limestone, apparently deriving from the bodies of ancient shelled creatures. These entities from the limestone still retained their activity; the only factor that stopped them was heat. Using the syllable ‘-zyme’ to indicate that the active principle here was of ‘fermentation’ or activity, he named the tiny objects ‘microzymas’.

What Béchamp talks about is a foundational concept. It describes a model of biology and cell function totally different from that that which forms the basis of most modern science. According to his experiments and observations, the microzymas possess a primary role in sustaining (and terminating) all life.

As Bechamp put it, life is the prey of life. When a creature dies, the microzymas take up the role of breaking it down and returning its elements to nature, where they are then taken up by other life-forms to be re-used. This cycle underpins all of life and material reality.

The Indian scientist Jagadish Bose would agree with this, and likely add that it applies to not only organic, but also inorganic matter; but that is another discussion.

Because of this basic incomptability of pleomorphism with the germ-based theory of Pasteur and his followers, Antoine Bechamp has been virtually written out of history. Look for him in any edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica – you won’t find him. Search in vain through most textbooks for his name, or for any mention of his work. He has been ‘unpersoned’ in an almost Orwellian manner.

One day, Béchamp will be restored to the status he deserves: a medical pioneer and truthseeker who was far ahead of his time.

Books from A Distant Mirror

Reading almost like a scientific detective story,BECHAMP OR PASTEUR? details the conflict between the two scientists. With full references to the proceedings of the French Academy of Sciences. It is ideal if you wish to understand the significance of Bechamp’s work, and why certain interests would want all mention of it removed from the scientific record.

Available in paperback, hardcover, and Epub.

The introduction by R. Pearson, originally published as Pasteur, Plagiarist, Imposter, is posted here, and the charts and related discussion are here.

An audiobook version of R. Pearson’s The Dream and Lie of Louis Pasteur (auto-generated, and pretty good), which is the introduction of this book, is free (like everything there) on Archive.org.

THE BLOOD AND ITS THIRD ELEMENT, by Antoine Bechamp, contains both an overview of the pleomorphic theory and detailed accounts of Bechamp’s experiments. This is a detailed scientific read, but the information in it is valuable. This was Bechamp’s last book, and summarises his life’s work. Available in paperback, Kindle and Epub.

Other researchers

“Later researchers like Naessens and Enderlein followed the same line of reasoning and developed their own systems of how these microzymas operate. Although their ideas were never proven false by opposing research, they were generally persecuted by mainstream medicine, which makes sense. Because without an enemy that can be identified and killed, what good is it to develop weapons? And developing weapons, that is, drugs, has been the agenda of the industry set up by Carnegie and Rockefeller even down to the present day, as we shall see. New drugs mean new research funding and government money and the need for prescriptions and for an entire profession to write those prescriptions.”

— The Post-Antibiotic Age: Germ Theory, Tim O’Shea

Royal Rife

Despite the dominance of Pasteur’s ‘germ theory’, Bechamp’s tiny ‘microzymas’ have been successfully ‘rediscovered’ several times in the 20th century, for example by ROYAL RIFE using his own revolutionary microscope to observe the particles changing into four different types. Rife handmade all the components of his microscopes, which could have thousands of operational parts.

Gaston Naessens

Later, working independently and with a different powerful microscope of his own invention, the French scientist GASTON NAESSENS observed these particles morph into sixteen different forms – including bacterial and fungal – which he called ‘somatids’. The significance of this: what we think of as pathogens are not necessarily “infectious” (or “exogenous”, or from outside), but can be “endogenous” (from within).

Gunther Enderlein

The German scientist GUNTHER ENDERLEIN (1872-1968) identified the same entities and called them ‘protits’.

Philippa Uwins

While at the University of Queensland during the 1990s, Dr Uwins found within samples of sandstone rock entities which she called nanodes. Evidence suggested that they are Bechamp’s microzymas and Naessens’ somatids. There are more details and links in this post about her work, and this transcript of a radio interview.

Common themes and findings link the work of these researchers. They may use various names for what they’ve found – microzyma, somatid, nanobe, protit – but the reality that they describe is consistent. Modern research continues to confirm and build upon Bechamp’s work.

Nothing in the new quantum biology and epigenetics would surprise Bechamp.

PLEASE EMAIL ANY INFORMATION, MATERIAL AND LINKS REGARDING THE WORK OF PROFESSOR BECHAMP TO editorial@adistantmirror.com