The following is the Introduction to The Problem of Increasing Human Energy.

- The onward movement of humanity.

- The energy of the movement.

- The three ways of increasing human energy.

Of all the endless variety of phenomena which nature presents to our senses, there is none that fills our minds with greater wonder than that inconceivably complex movement which we designate as human life. Its mysterious origin is veiled in the forever impenetrable mist of the past, its character is rendered incomprehensible by its infinite intricacy, and its destination is hidden in the unfathomable depths of the future.

From where does it come? What is it? Where is it going? are the great questions which the sages of all times have endeavored to answer.

Modern science says that the sun is the past, the earth is the present, the moon is the future; in other words, from an incandescent mass we originated, and into a frozen mass we shall eventually turn.

The law of nature is merciless, and rapidly and irresistibly we are drawn to our doom.

Lord Kelvin, in his profound meditations, allows humanity only a short span of life, something like six million years, after which time the sun’s light will have ceased to shine, and its life-giving heat will have ebbed away. Our own earth will become a lump of ice, hurrying on through an eternal night.

But do not let us despair. There will still be left upon the Earth a glimmering spark of life, and there will be a chance to kindle a new fire on some distant star.

This wonderful possibility seems, indeed, to exist, judging from Professor Dewar’s beautiful experiments with liquid air, which show that the germs of organic life are not destroyed by cold, no matter how intense.

Consequently, they may be transmitted through interstellar space.

Meanwhile the lights of science and art, ever increasing in intensity, illuminate our path, and the marvels they disclose, and the enjoyments they offer, make us forgetful of the gloomy future.

Though we may never be able fully to comprehend human life, we know certainly that it is a movement, of whatever nature it may be. The existence of movement unavoidably implies a body which is being moved, and a force which is moving it.

Hence, wherever there is life, there is a mass moved by a force. All mass possesses inertia, all force tends to persist.

Owing to this universal property and condition, a body, be it at rest or in motion, tends to remain in the same state. A force, manifesting itself anywhere and through whatever cause, produces an equivalent opposing force. As an absolute necessity of these two facts, it follows that every movement in nature must be rhythmical.

Long ago this simple truth was clearly pointed out by Herbert Spencer, who arrived at it through somewhat different reasoning. It is borne out in everything we perceive—in the movement of a planet, in the surging and ebbing of the tide, in the reverberations of the air, the swinging of a pendulum, the oscillations of an electric current, and in the infinitely varied phenomena of organic life.

Does not the whole of human life attest to it? Birth, growth, old age, and death of an individual, family, race, or nation; what is it all but a rhythm?

All life manifestation, then, even in its most intricate form, as exemplified in man, however involved and inscrutable, is only a movement, to which the same general laws of movement which govern the entire physical universe must be applicable.

When we speak of ‘man’, we mean humanity as a whole, and before applying scientific methods to the investigation of his movement, we must accept this as a physical fact. But can anyone doubt today that all the millions of individuals and all the innumerable types and characters constitute an entity, a unit?

Though free to think and act, we are held together, like the stars in the firmament, with ties that make us inseparable. These ties cannot be seen, but we can feel them. I cut myself in the finger, and it pains me: this finger is part of me. I see a friend hurt, and it hurts me, too: my friend and I are one. And now I see an enemy stricken down, a lump of matter which, of all the lumps of matter in the universe, I care least for, and yet it still grieves me. Does this not prove that each of us is part of a whole?

For ages, this idea has been proclaimed in the consummately wise teachings of religion, probably not alone as a means of insuring peace and harmony among men, but as a deeply founded truth. The Buddhist expresses it in one way, the Christian in another, but both say the same: we are all one.

Metaphysical proofs are, however, not the only ones which we are able to bring forth in support of this idea.

Science, too, recognizes this connectedness of separate individuals, though not quite in the same sense as it admits that the suns, planets, and moons of a constellation are one body. There can be no doubt that it will be experimentally confirmed in times to come, when our means and methods of investigating psychical and other states and phenomena shall have been brought to great perfection.

And this collective human being lives on and on. The individual is ephemeral and short-lived, and races and nations rise and pass away, yet humanity as a whole remains.

Therein lies the profound difference between the individual and the whole. Therein, too, is to be found the partial explanation of many of those marvelous phenomena of heredity which are the result of countless centuries of feeble but persistent influence.

Consider, then, man as a mass urged on by a force. Though this movement is not of a translatory character, implying change of place, the general laws of mechanical movement are nevertheless applicable to it, and the energy associated with this mass can be measured, in accordance with well-known principles, by half the product of the mass with the square of a certain velocity.

So, for instance, a cannon ball which is at rest possesses a certain amount of energy in the form of heat, which we measure in a similar way. We imagine the ball to consist of innumerable minute particles, called atoms or molecules, which vibrate or whirl around one another. We determine their masses and velocities, and from them the energy of each of these minute systems, and adding them all together, we get an idea of the total heat energy contained in the ball, which is only seemingly at rest.

In this purely theoretical estimate this energy may then be calculated by multiplying half of the total mass—that is, half of the sum of all the small masses—with the square of a velocity which is determined from the velocities of the separate particles.

In like manner, we may conceive of human energy being measured by half the human mass multiplied with the square of the velocity which we are not yet able to compute. But our deficiency in this knowledge will not vitiate the truth of the deductions I shall draw, which rest on the firm basis that the same laws of mass and force govern throughout nature.

Man, however, is not an ordinary mass, consisting of spinning atoms and molecules, and containing merely heat energy. He is a mass possessed of certain higher qualities by reason of the creative principle of life with which he is endowed. His mass, as the water in an ocean wave, is being continuously exchanged, new taking the place of the old.

Not only this, but he grows, propagates, and dies, thus altering his mass independently, both in bulk and density. What is most wonderful of all, he is capable of increasing or diminishing his velocity of movement by using the mysterious power he possesses by appropriating more or less energy from other substances, and turning it into motive energy.

But in any given moment we may ignore these slow changes and assume that human energy is measured by half the product of man’s mass with the square of a certain hypothetical velocity. However we may compute this velocity, and whatever we may take as the standard of its measure, we must, in harmony with this conception, come to the conclusion that the great problem of science is, and always will be, to increase the energy thus defined.

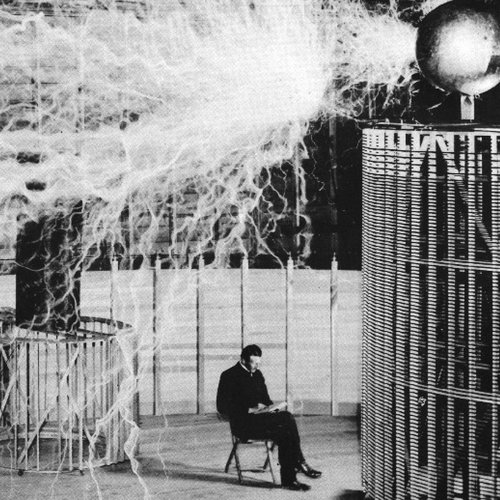

Many years ago, stimulated by my study of that deeply interesting work, Draper’s History of the Intellectual Development of Europe, which depicts human movement so vividly, I recognized that to solve this eternal problem must be the chief task of science. Some results of my own efforts I shall describe here.

Be the first to comment