AMAZON PAPERBACK | US | UK | Germany | France | Spain | Italy | Japan | Canada | Australia | Sweden | Poland | Netherlands

PAPERBACK ELSEWHERE | Barnes & Noble | Books-A-Million | Book Depository | Independent Bookstores | Book Depository | Fishpond

AMAZON KINDLE | US | UK | Germany | France | Spain | Italy | Netherlands | Japan | Brazil | Canada | Mexico | Australia | India

EBOOK ELSEWHERE | Google

EBOOK HERE | PDF | Epub

AUDIOBOOK | Amazon | Google Play | B&N | Kobo | Scribd

Google’s NotebookLM discusses Marais’s work and its importance:

DOWNLOAD SAMPLE PDF

“Strange. Esoteric. Dark. And strangely beautiful. An amateur biologist/entomologist heads into the veldt with a supply of morphine and a magnifying glass to study termites. And it’s as weird as that setup sounds. And because of that, it’s as different and enlightening as anything I’ve read on the natural sciences, integrating the observer’s soul and mind into the deep caverns of the termite.”

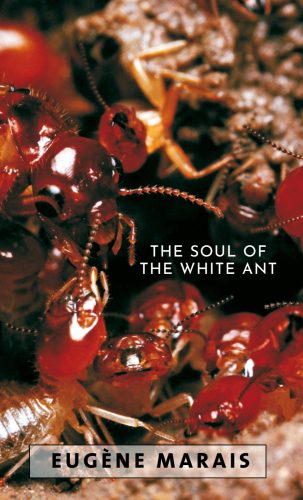

The Soul of the White Ant by Eugène Marais is a passionate, insightful account into the world of termites. It is a meticulously researched expose of their complex, highly structured community life.

Originally translated into English in 1937, the quality of research remains as relevant today as it was when it was first published. This illuminating account will not only appeal to those with a scientific interest in termites, but will similarly enthrall readers who are new to their captivating world.

An exceptional feature of his detailed research is the extraordinary psychological life of the termite. While the studies are based in South Africa, the extensive research includes the termites of Magnetic Island, Australia.

The Soul of the White Ant is part science, part mysticism, a sort of manual of pantheism, and a very personal and careful observation of termites as a life form.

“As a safari Guide in the Okavango Botswana for many years, I used this book as a basis for presenting a fascination for the smaller creatures of the African bush, my home for my entire life and which I was privileged to share with many clients from different countries. Termite mounds are really interesting and Eugene Marais compared the infrastructure of a termitary to that of the human body. Writing from the heart, this scientific author instills a wonder in the reader, of the incredible intricacies of nature, in a light-hearted, easily readable manner.”

“An excellent read – astonishing for it’s time. A heartfelt and truly holistic/metaphysical observation of how the colony functions which is deeply thought provoking…”

Contents

1 / The Beginning of a Termitary

2 / Unsolved Secrets

3 / Language in the Insect World

4 / What is the Psyche?

5 / Luminosity in the Animal Kingdom

6 / The Composite Animal

7 / Somatic Death

8 / The Development of the Composite Animal

9 / The Birth of the Termite Community

10 / Pain and Travail in Nature

11 / Uninherited Instincts

12 / The Mysterious Power which Governs

13 / The Water Supply

14 / The First Architects

15 / The Queen in her Cell

Eugene Marais

Marais’ work as a naturalist, although by no means trivial (he was one of the first scientists to practice ethology and was repeatedly acknowledged as such by Robert Ardrey and others), gained less public attention and appreciation than his contributions as a literalist.

He discovered the Waterberg Cycad, which was named after him (Encephalartos eugene-maraisii).

He was the first person to study the behaviour of wild primates and his observations continue to be cited in contemporary evolutionary biology. He is amongst the greatest of the Afrikaner poets and remains one of the most popular, although his output was not large. Opperman described him as the first professional Afrikaner poet; Marais believed that craft was as important as inspiration for poetry. Along with J.H.H. de Waal and G.S. Preller, he was a leading light in the Second Afrikaans (language) Movement in the period immediately after the Second Boer War, which ended in 1902.

Some of his finest poems deal with the wonders of life and nature but he also wrote about inexorable Death.

Marais was isolated in some of his beliefs. He was a self-confessed pantheist and claimed that the only time he entered a church was for weddings. Although an Afrikaner patriot, Marais was sympathetic to the cultural values of the black tribal peoples of the Transvaal; this is seen in poems such as Die Dans van die Reën (The dance of the rain). The following translation of Marais’ Winternag is by J. W. Marchant:

Winter’s Night

O the small wind is frigid and spare

and bright in the dim light and bare

as wide as God’s merciful boon

the veld lies in starlight and gloom

and on the high lands

spread through burnt bands

the grass-seed, astir, is like beckoning hands.O East-wind gives mournful measure to song

Like the lilt of a lovelorn lass who’s been wronged

In every grass fold

bright dewdrop takes hold

and promptly pales to frost in the cold!

Be the first to comment