A biography of Antoine Bechamp

The following is the original translator’s preface to The Blood and its Third Element.

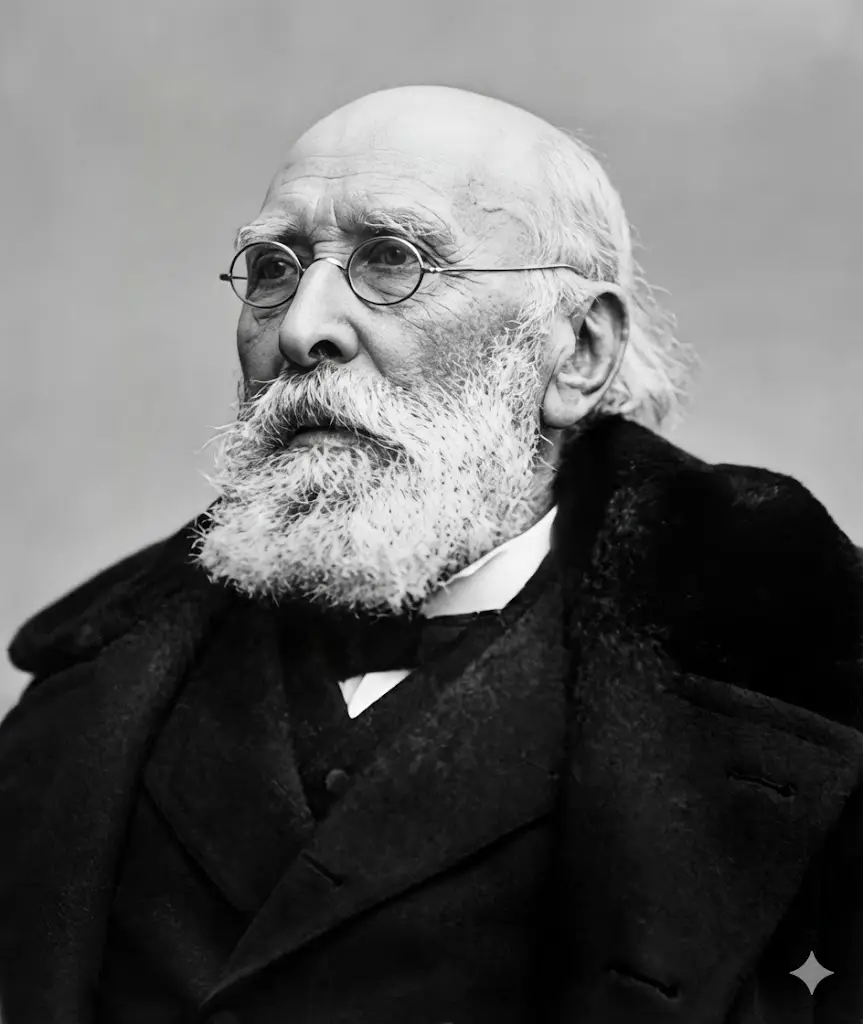

On October 16th, 1816, at Bassing, in the department of Bas-Rhein, was born a child by whose name the nineteenth century will come to be known, as are the centuries of Copernicus, Galileo and Newton by their names.

Antoine Béchamp died on the 15th April, 1908, fourteen days after he was first visited by an aged American physician between whom and himself a correspondence had passed for several years on the subject of the researches and wonderful discoveries of Professor Béchamp and his collaborators. The American physician made his visit to Paris for the purpose of becoming personally acquainted with the Professor, who, as his family stated, had looked forward with eager anticipation to such a visit.

The translator had long previously submitted an extensive summary of the professor’s physiological and biological discoveries, by whom it was revised and approved.

This was intended to be introduced as a special chapter in an extensive work on inoculations and their relations to pathology,upon which the translator of this work had been engaged, almost exclusively, for some fourteen years.

But in the lengthy and nearly daily interviews between Professor Béchamp and myself, which, as just shown, closely preceded the former’s death, I suggested that instead of such summary it would be better to place before the English speaking peoples an exact translation into their language of some, at least, of the more important discoveries of Professor Béchamp—especially as, in my opinion, it would not be easy to carry out among them the conspiracy of silence by means of which his discoveries had been buried in favour of distorted plagiarisms of his labours which had been productive of such abortions as the microbian or germ theory of disease, “the greatest scientific silliness of the age,” as it has been correctly styled by Professor Béchamp.

To this suggestion Professor Béchamp gave hearty assent, and told me to proceed exactly as I might think best for the promulgation of the great truths of biology, physiology, and pathology discovered by him, and authorised me to publish freely either summaries or translations into English, as I might deem most advisable.

As a result of this authorisation, the present volume is published, and is intended to introduce to peoples of the English tongue the last of the great discoveries of Professor Béchamp.

The subject of the work is described by its title, but it is well to remind the medical world and to inform the lay public that the problem of the coagulation of the blood, so beautifully solved in this volume, has until now been an enigma and opprobrium to biologists, physiologists and pathologists.

The professor was in his 85th year at the time of the publication of the work here translated. To the best of the translator’s knowledge it has not yet been plagiarised, and is the only one of the Professor’s more important discoveries which has not been so treated; but at the date of its publication the arch plagiarist (Pasteur) was dead,though his evil work still lives.

One of the discoveries of Béchamp was the formation of urea by the oxidation of albuminoid matters. The fact, novel at the time, was hotly disputed, but is now definitely settled in accordance with Béchamp’s view. His memoir described in detail the experimental demonstration of a physiological hypothesis of the origin of the urea of the organism, which had previously been supposed to proceed from the destruction of nitrogenous matters.

By a long series of exact experiments, he demonstrated clearly the specificity of the albuminoid matters and he fractionised into numerous defined species albuminoid matters which had until then been described as constituting a single definite compound.

He introduced new yet simple processes of experimentation of great value, which enabled him to publish a list of definite compounds and to isolate a series of soluble ferments to which he gave the name of zymases. To obscure his discoveries, the name of diastases has often been given to these ferments, but that of zymas must be restored. He also showed the importance of these soluble products (the zymases) which are secreted by living organisms.

He was thus led to the study of fermentations. Contrary to the then generally accepted chemical theory, he demonstrated that the alcoholic fermentation of beer yeast was of the same order as the phenomena which characterise the regular performance of an act of animal life—digestion.

In 1856, he showed that moulds transformed cane sugar into invert sugar (glucose) in the same manner as does the inverting ferment secreted by beer yeast. The development of these moulds is aided by certain salts, impeded by others, but without moulds there is no transformation.

He showed that a sugar solution treated with precipitated calcic carbonate does not undergo inversion when care is taken to prevent the access to it of external germs, whose presence in the air was originally demonstrated by him.If to such a solution the calcareous rock of Mendon or Sens be added instead of pure calcic carbonate, moulds appear and the inversion takes place.

These moulds, under the microscope, are seen to be formed by a collection of molecular granulations which Béchamp named microzymas. Not found in pure calcic carbonate, they are found in geological calcareous strata, and Béchamp established that they were living beings capable of inverting sugar, and some of them to make it ferment. He also showed that these granulations under certain conditions evolved into bacteria.

To enable these discoveries to be appropriated by another, the name microbe was later applied to them, and this term is better known than that of microzyma; but the latter name must be restored, and the word microbe must be erased from the language of science into which it has introduced an overwhelming confusion. It is also an etymological solecism.

Béchamp denied spontaneous generation, while Pasteur continued to believe it. Later he, too, denied spontaneous generation, but he did not understand his own experiments, and they are of no value against the arguments of the sponteparist Pouchet, which could be answered only by the microzymian theory. So, too, Pasteur never understood either the process of digestion nor that of fermentation, both of which processes were explained by Béchamp, and by a curious imbroglio (was it intentional?) both of these discoveries have been ascribed to Pasteur.

That Lister did, as he said, most probably derive his knowledge of antisepsis (which Béchamp had discovered) from Pasteur is rendered probable by the following peculiar facts.

In the earlier antiseptic operations of Lister, the patients died in great numbers, so that it came to be a gruesome sort of medical joke to say that “the operation was successful, but the patient died.” But Lister was a surgeon of great skill and observation, and he gradually reduced his employment of antiseptic material to the necessary and not too large dose, so that his operations “were successful and his patients lived.”

Had he learned his technique from the discoverer of antisepsis, Béchamp, he would have saved his earlier patients; but deriving it second hand from a savant (sic) who did not understand the principle he was plagiarising, Lister had to acquire his subsequent knowledge of the proper technique through his practice, i.e. at the cost of his earlier patients.

Béchamp carried further the aphorism of Virchow—Omnis cellula e cellula—which the state of microscopical art and science at that time had not enabled the latter to achieve. Not the cellule but the microzyma must, thanks to Béchamp’s discoveries, be today regarded as the unit of life, for the cellules are themselves transient and are built up by the microzymas, which, physiologically,are imperishable, as he has clearly demonstrated.

Béchamp studied the diseases of the silk worm then (1866) ravaging the southern provinces of France and soon discovered that there were two of them—one, the pébrine, which is due to a parasite; the other, the flacherie, which is constitutional.

A month later, Pasteur, in a report to the Academy of his first silkworm campaign, denied the parasite, saying of Béchamp’s observation, “that is an error.” Yet in his second report, he adopted it, as though it were his own discovery!

The foregoing is but a very imperfect list of the labours and discoveries of Antoine Béchamp, of which the work here translated was the crowning glory.

The present work describes the latest of all the admirable biological discoveries of the Professor Béchamp. It is proposed to follow it up with a translation of The Theory of the Microzymas and the Microbian System now in course of translation; and The Microzymas, the translation whereof is completed. Other works will, it is hoped, follow, viz.: The Great Medical Problems, the first part of which is ready for the printer, Vinous Fermentation, translation complete; and New Researches upon the Albuminoids, also complete.

The study of these and of the other discoveries of Professor Béchampwill produce a new departure and a sound basis for the sciences of biology, of physiology and of pathology, today floating in chaotic uncertainty and confusion; and will, it is hoped, bring the medical profession back to the right path of investigation and of practice from which it has been led astray into the microbian theory of disease, which, as before mentioned, was declared by Béchampto be the “greatest scientific silliness of the age.”

– Montague R. Leverson